I was duped into leaving London for school in Ghana - but it saved me

- BBC News

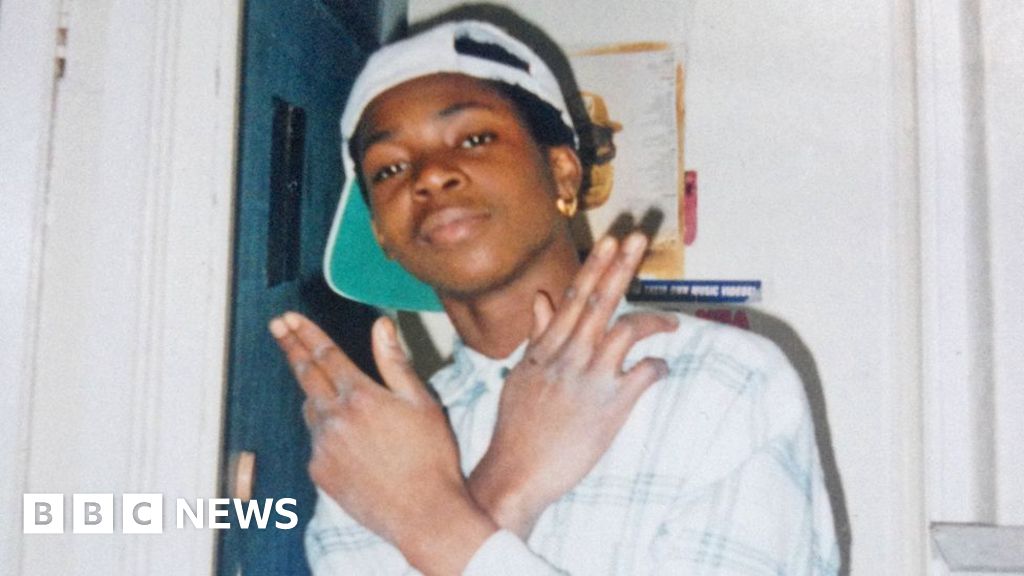

When my mother told me at the age of 16 that we were going from the UK to Ghana for the summer holidays, I had no reason to doubt her.

It was just a quick trip, a temporary break - nothing to worry about. Or so I thought.

One month in, she dropped the bombshell - I was not coming back to London until I had reformed and had earned enough GCSEs to continue my education.

I was hoodwinked in a similar way to the British-Ghanaian teenager who recently took his parents to the High Court in London for sending him to school in Ghana.

In their defence, they told the judge they did not want to see their 14-year-old son become "yet another black teenager stabbed to death in the streets of London".

Back in the mid-1990s, my mother, a primary school teacher, was motivated by similar concerns.

I had been excluded from two high schools in the London Borough of Brent, hanging out with the wrong crowd (becoming the wrong crowd) - and heading down a dangerous path.

My closest friends at the time ended up in prison for armed robbery. Had I stayed in London, I would have almost certainly been convicted with them.

But being sent to Ghana also felt like a prison sentence.

I can empathise to a degree with the teenager, who said in his court statement that he feels like he is "living in hell".

Yet, speaking for myself, by the time I turned 21 I realised what my mother had done had been a blessing.

Unlike the boy at the centre of the London court case - which he lost - I did not go to boarding school in Ghana.

My mother placed me in the care of her two closest brothers, they wanted to keep an eye on me and it was felt that being around boarders could prove too much of a distraction.

I first stayed with my Uncle Fiifi, a former UN environmentalist, in a town called Dansoman, near the capital, Accra.

The lifestyle change hit hard. In London, I had my own bedroom, access to washing machines and a sense of independence - even if I was using it recklessly.

In Ghana, I was waking up at 05:00 to sweep the courtyard and wash my uncles often muddy pick-up truck and my aunts car.

It was her vehicle that I would later steal - something of a watershed moment.

I did not even know how to drive properly, treating a manual like an automatic and I crashed it into a high-ranking soldiers Mercedes.

I tried to flee the scene. But that soldier caught me and threatened to take me to Burma Camp, the notorious military base where people had disappeared in the past.

That was the last truly reckless thing I did.

It was not just discipline that I learnt in Ghana - it was perspective.

Life in Ghana showed me how much I had taken for granted.

Washing clothes by hand and preparing meals with my aunt made me appreciate the effort needed.

Food, like everything in Ghana, required patience. There were no microwaves, no fast-food runs.

Making the traditional dough-like dish fufu, for example, is laborious and involves pounding cooked yams or cassava into a paste with a mortar.

At the time, it felt like punishment. Looking back, it was building resilience.

Initially, my uncles considered placing me in high-end schools like the Ghana International School or SOS-Hermann Gmeiner International College.

But they were smart. They knew I might just form a new crew to cause chaos and mischief.

Instead, I received private tuition at Accra Academy, a state secondary school that my late father had attended. It meant I was often taught on my own or in small groups.

Lessons were in English, but out of school those around me were often speaking local languages and I found it easy to pick them up perhaps because it was such an immersive experience.

Back home in London, I used to love to learn swear words in my mothers Fante language - but was far from fluent.

When I later moved to the city of Tema to stay with my favourite uncle, Uncle Jojo - an agricultural expert, I continued private tuition at Tema Secondary School.

In contrast to the boy making the headlines in the UK, who claimed Ghanas education system was not up to standard, I found it to be exacting.

I was considered academically gifted in the UK, despite my troublesome ways, but actually found it tough going in Ghana. Students my age were far ahead in subjects like maths and science.

The rigour of the Ghanaian system pushed me to study harder than I ever had in London.

The result? I earned five GCSEs with grades C and above - something that once seemed impossible.

Beyond academic achievements, Ghanaian society instilled values that have stayed with me for life.

Respect for elders was non-negotiable. Throughout the neighbourhoods I lived in, you greeted those older than you, regardless of whether or not you knew them.

Ghana did not just make me more disciplined and respectful - it made me fearless.

Football played a huge part in that transformation. I played in the parks, which were often hard red clay with loose pebbles and stones, with two square goalposts fashioned out of wood and string.

It was a far cry from the neatly maintained pitches in England, but it toughened me up in ways I could not have imagined - and it is no wonder some of the greatest footballers seen in the English Premier League have come from West Africa.

The aggressive style played in Ghana was not just about skill - it was about resilience and endurance. Getting tackled on rough ground meant picking yourself up, dusting yourself off and carrying on.

Every Sunday, I played football on the beach - though I would often be late because there was absolutely no way either of my uncles would allow me to stay home instead of attending church.

Those services felt like they lasted forever. But it was also a testament to Ghana as a God-fearing nation, where faith is deeply embedded in everyday life.

The first 18 months were the hardest. I resented the restrictions, the chores, the discipline.

I even tried stealing my passport to fly back to London, but my mother was ahead of me and had hidden it well. There was no escape.

My only choice was to adapt. Somewhere along the way, I stopped seeing Ghana as a prison and started seeing it as happy home.

I know of a few others like me who were sent back to Ghana by their parents living in London.

Michael Adom was 17 when he arrived in Accra for school in the 1990s, describing his experience as "bittersweet". He stayed until he was 23 and now lives back in London working as a probation officer.

His main complaint was the loneliness - he missed his family and friends. There were times of anger about his situation and the complications of feeling misunderstood.

This largely stemmed from the fact that his parents had not taught him or his siblings any of the local languages when growing up in London.

"I didnt understand Ga. I didnt understand Twi. I didnt understand Pidgin," the 49-year-old tells me.

This made him feel vulnerable for his first two-and-a-half years - and, he says, liable to being fleeced, for example, by those increasing prices because he seemed foreign.

"Anywhere I went, I had to make sure I went with somebody else," he says.

But he ended up becoming fluent in Twi and, overall, he believes the positives outweighed the negatives: "It made me a man.

"My Ghana experience matured me and changed me for the better, by helping me to identify with who I am, as a Ghanaian, and cemented my understanding of my culture, background and family history."

I can concur with this. By my third year, I had fallen in love with the culture and even stayed on for nearly two more years after passing my GCSEs.

I developed a deep appreciation of the local food. Back in London, I never thought twice about what I was eating. But in Ghana, food was not just sustenance - each dish had its own story.

I became obsessed with "waakye" - a dish made from rice and black-eyed peas, often cooked with millet leaves, giving it a distinctive purple-brown colour. It was usually served with fried plantain, the spicy black pepper sauce "shito", boiled eggs, and sometimes even spaghetti or fried fish. It was the ultimate comfort food.

I enjoyed the music, the warmth of the people and the sense of community. I was not just "stuck" in Ghana any more - I was thriving.

My mother, Patience Wilberforce, passed away recently, and with her loss I have reflected deeply on the decision she made all those years ago.

She saved me. Had she not tricked me into staying in Ghana, the chances of me having a criminal record or even serving time in prison would have been extremely high.

I went on to enrol at the College of North West London aged 20 to study media production and communications, before joining BBC Radio 1Xtra via a mentoring scheme.

The guys I used to hang out with in north-west London did not get the second chance that I did.

Ghana reshaped my mindset, my values and my future. It turned a misguided menace into a responsible man.

While such an experience might not work for everyone, it gave me the education, discipline and respect I needed to reintegrate into society when I returned to England.

And for that, I am forever indebted to my mother, to my uncles and to the country that saved me.

Mark Wilberforce is a freelance journalist based in London and Accra.

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica