Mohamed Salah - Egyptian king

- BBC News

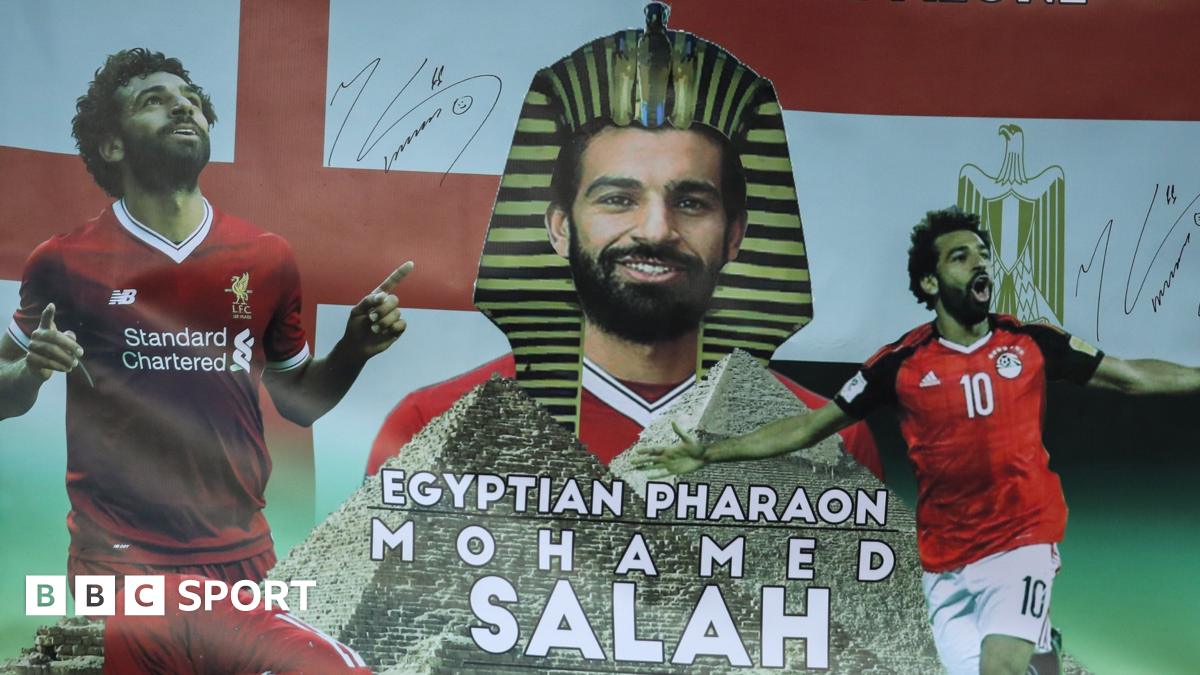

Mohamed Salah - Egyptian king

"Whenever I walk in here, I cant help but recall how he used to move and the way he controlled the ball. It was something else."

One of Mohamed Salahs first coaches is opening the all-new dark green gates of the youth centre in Nagrig, a village about three hours north of Cairo. This is where it all began for one of the worlds most prolific forwards - a player who propelled Liverpool to the Premier League title in May.

It was on the streets of Nagrig where a seven-year-old Salah, external would play football with his friends, pretending to be Brazil striker Ronaldo, Frances legendary playmaker Zinedine Zidane or Italian maestro Francesco Totti.

"Mohamed was small compared to his team-mates, but he was doing things even the older boys couldnt manage," Ghamry Abd El-Hamid El-Saadany says as he points to the artificial pitch which is now named in Salahs honour.

"His shots were incredibly powerful, and it was obvious that he had determination and drive."

Salah, 33, is about to embark on his ninth season at Liverpool, where the winger has scored a remarkable 245 goals in 402 league and cup appearances since joining in 2017.

Egypts first global football superstar has won every domestic honour as well as the Champions League with the Reds, but has yet to taste success with his country.

With the Africa Cup of Nations in December and the 2026 World Cup on the horizon, BBC Sport visited Egypt to discover what Salah means to the people of the football-mad country of 115 million, and how a small boy from humble beginnings became a national icon.

"I still feel my fathers joy when I watch Salah," says Lamisse El-Sadek, at the Dentists Cafe in the east of Cairo. "After Salah joined Liverpool, we used to watch every match on television together."

The cafe is named after the former owners original profession and is now where Liverpool fans gather to watch matches on the big screen.

Lamisse is wearing a Liverpool shirt with her fathers name on the back. "He sadly passed away two years ago," she adds.

"Every Liverpool game was some of the happiest two hours in our household every week and even if I had to miss some of the game due to school or work, my father used to text me minute-by-minute updates.

"Salah didnt come from a class of privilege. He really worked hard and sacrificed a lot to reach where he is now. A lot of us see ourselves in him."

You can listen to the full version of Mohamed Salah: The Egyptian King here.

Children in Nagrig, where Salah was born and raised, dream of following in the players footsteps

The small farming village of Nagrig in the Egyptian Nile Delta is nestled in swathes of green fields, growing jasmine and watermelons. Water buffalos, cows and donkeys share dirt roads with cars, motorbikes and horse-drawn carts.

It is here where one of the worlds best and most prolific forwards, affectionately known as the Egyptian King, spent his early years.

"Salahs family is the foundation and secret behind his success," adds El-Saadany, who calls himself Salahs first coach after nurturing him when he was eight years old.

"They still live here with humility, values and respect. Thats one reason people love them so much."

The youth centre has been given an impressive upgrade recently in tribute to the villages most famous son, and the green playing surface would not look out of place at a professional training ground.

"They [Salahs family] made many sacrifices when he was young," says El-Saadany, who is standing next to a huge photograph that hangs behind one of the goals, showing Salah with the Champions League trophy.

"They were incredibly supportive from the very beginning, especially his father and his uncle, who is actually chairman of this centre."

Salahs footprint is everywhere in Nagrig, where children run around wearing Liverpool and Egypt shirts with the players name and number on the back.

There is a mural of Salah outside his old school, while a tuk-tuk rushes past beeping its horn with a large sticker of the player smiling on the front.

In the heart of Nagrig is the barbers shop where a teenage Salah would get his hair cut after training.

"Im the one who gave him that curly hairstyle and the beard," says Ahmed El Masri.

"His friends told him not to get his hair cut here because were from a village not a city, but hed always come to me. The next day his friends would be surprised [at how good he looked] and ask him whos your barber?."

Ahmed El Masri, the barber who used to cut Salahs hair, outside his shop in Nagrig

The hairdresser recalls watching Salahs skills at the youth centre and on the streets of the village.

"The big thing I remember most is that when we all played PlayStation, Salah would always choose to be Liverpool," he adds. "The other boys would choose Manchester United or Barcelona, but hed always be Liverpool.

"All the young kids now living in the village want to be like him."

Salahs football education included a six-year spell at Cairo-based club Arab Contractors, also known as Al Mokawloon.

He joined them at the age of 14 and the story of Salah being given permission to leave school early to make daily round trips, taking many hours, to train and play for Arab Contractors has become legendary in Egypt and beyond.

A tuk-tuk driver in Nagrig poses in front of his vehicle and a sticker of Salah on the windscreen

A couple of the passengers on board the cramped, seven-seater Suzuki van on the edge of Nagrig are getting jittery.

"Are they getting on or not?"

This is not a bus service which runs to a timetable. In fact, the driver only leaves when it fills up.

As a teenager this bus stop was where Salah started his long journey to training at Arab Contractors. "It was a tough journey and also incredibly expensive," El-Saadany says.

"He depended on himself and travelled alone most of the time. Imagine a child leaving at 10am and not returning until midnight. That journey required someone strong; only someone with a clear goal could bear such a burden."

When we do jump on the bus, we are squeezed at the back behind a mother and her two sons and we head in the direction of a city called Basyoun, the first stop on Salahs regular journey to Cairo.

He would then jump on another bus to Tanta, before changing again to get to the Ramses bus station in Cairo where there would be another switch before finally reaching his destination.

After the early evening sessions it was time for the same long trip back to Nagrig and the same regular changes in reverse.

The white microbuses darting around the roads at all hours are one of the first things you notice when you arrive in Cairo, packed with travellers hopping on and hopping off.

"These vehicles handle around 80% of commuters in a city home to over 10 million people," Egyptian journalist Wael El-Sayed explains.

"There are thousands of these vans working 24/7."

A microbus in Nagrig similar to the ones Salah used to travel on to get to Cairo and back several times a week

Just the small journey to Basyoun is tough in hot and uncomfortable conditions at the back of the bus, so you can only imagine how challenging the much longer journey, several times a week, would have been for a teenage Salah.

The coach who gave Salah his first international cap believes such experiences have helped provide the player with the mentality to succeed at the top level.

"To start as a football player here in Egypt is very hard," says Hany Ramzy.

Ramzy was part of the Egypt side that faced England, external at the 1990 World Cup and spent 11 years playing in the Bundesliga. He handed Salah his senior Egypt debut in October 2011 when he was interim manager of the national side.

He was also in charge of the Egypt Under-23 team that Salah played in at the London 2012 Olympics.

"I also had to take buses and walk five or six kilometres to get to my first club of Al Ahly and my father couldnt afford football boots for me," adds Ramzy.

"Salah playing at the top level and staying at the top level for so many years was 100% shaped by this because this kind of life builds strong players."

Mohamed Salah joined Liverpool from Roma for £34m in June 2017

Driving into Cairo over one of its busiest bridges, a huge electronic billboard flicks from an ice cream advert to a picture of Salah next to the Arabic word shukran, which means thank you.

Waiting at a nearby office is Diaa El-Sayed, one of the most influential coaches in Salahs early career.

He was the coach when Salah made his first impact on the global stage, at the 2011 Under-20 World Cup in Colombia.

"The country wasnt stable, there was a revolution, so preparing for the tournament was tough for us," says the man everyone calls Captain Diaa.

"Salah came with us and the first thing that stood out was his speed and that he was always concentrating. Hes gone far because he listens so well, no arguments with anyone, always listening and working, listening and working. He deserves what he has."

Captain Diaa recalls telling a young Salah to stay away from his own penalty area and just concentrate on attacking.

"Then against Argentina, external he came back to defend in the 18-yard box and gave away a penalty," he says, laughing.

"I told him, dont defend, why are you in our box? You cant defend!.

"After Liverpool won the Premier League title last season, I heard him saying Arne Slot tells him not to defend. But I was the first coach who told him not to defend."

A mural of Salah outside a cafe in Cairo

Salah has played for the senior national team for 14 years and his importance to Egypt is such that high-ranking government officials have been known to get involved when he has been injured.

"I even had calls from Egypts Minister of Health," recalls Dr Mohamed Aboud, the national teams medic, about the time Salah suffered a serious shoulder injury in Liverpools defeat to Real Madrid in the 2018 Champions League final, leading to speculation he could miss the World Cup in Russia a few weeks later.

"I told him not to panic, everything is going well."

Speaking from his medical clinic in the Maadi area of Egypts capital, Dr Aboud adds: "I was younger and the pressure from inside the country was intense.

"I had calls from so many people trying to help. One of our board members told me I was now one of the most important people in the whole world.

"This situation changed me as a person."

For the record, Salah did recover to play in two of his countrys three group games but was unable to prevent Egypt from making a quick exit after defeats to Uruguay, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

"I need to tell you that Salah was involved in every single goal in our 2018 World Cup qualification campaign," says former Egypt assistant coach Mahmoud Fayez at his home on the outskirts of Cairo.

Salah had scored a dramatic 95th-minute penalty against Congo in Alexandria to secure a 2-1 win and book Egypts place at the World Cup, with one qualifying game to spare, for the first time in 28 years.

In a nail-biting game, Salah put Egypt ahead before Congo equalised three minutes from time.

"Do you know when you can listen to silence? I listened to the silence when Congo scored - 75,000 fans and silence everywhere," adds Fayez.

Then came the penalty that turned Salah into a national hero.

"Imagine it, a nation of nearly 120 million waiting for this moment to qualify," says Fayez. "He had the toughest and most difficult moment for one player, a penalty in the 95th minute that Mohamed had to score.

"He scored it and he made us all proud. In the dressing room afterwards he started to dance, hug everyone and he was shouting we did it, we did it, after 28 years, we did it."

In Cairo is a football academy called The Maker, founded and run by former Tottenham and Egypt striker Mido, who is hoping to produce players who will follow in Salahs footsteps.

"I played for the national team in front of 110,000 people when I was only 17, the youngest player to represent Egypt," Mido says. "I love to feel that people depend on me and Salah is the same."

At the time of our visit, a classroom lesson for young players about the mindset required to become a top professional is taking place.

Underneath Salahs name on a whiteboard, one of the coaches has written "discipline, dedication and motivation".

"The reason Salah is where he is now is because he works on his mental strength daily," Mido adds.

"He is the greatest ambassador for Egypt and for African players as well. He made European clubs respect Arab players, this is what Salah has done.

"I think a lot of European clubs now, when they see a young player from Egypt, they think of Salah. He has made our young players dream."

Back to Nagrig and we meet Rashida, a 70-year-old who sells vegetables from a small stall. She talks about how Salah has changed her life and the lives of hundreds of other people in the village where he was born and raised.

"Mohamed is a good man. Hes respectful and kind, hes like a brother to us," Rashida says.

She is one of many people in the village who have benefited from the work of Salahs charity, which gives back to the place where his journey to football stardom started.

"The aim is to help orphans, divorced and widowed women, the poor, and the sick," says Hassan Bakr from the Mohamed Salah Charity Foundation.

"It provides monthly support, meals and food boxes on holidays and special occasions. For example [with Rashida] theres a supplement to the pension a widow receives.

"When Mohamed is here he stays humble, walking around in normal clothes, never showing off. People love him because of his modesty and kindness."

As well as the charity helping people like Rashida, Salah has funded a new post office to serve the local community, an ambulance unit, a religious institute and has donated land for a sewage station, among other projects.

When Liverpool won the English league title for a record-equalling 20th time last season, fans turned up at a local cafe in Nagrig to watch on television and celebrate the villages famous son.

With there be more celebrations in Salahs home village in 2025-26?

Despite helping Liverpool to the Premier League title in 2019-20 and 2024-25, the player has yet to lift a trophy for his country.

The generation before Salah won three Africa Cup of Nations titles in a row between 2006 and 2010. Since then, there have been two defeats in finals, against Cameroon in 2017 and Senegal in the 2021 edition, which took place in early 2022.

With the 2025 Africa Cup of Nations starting on 21 December - six months before the World Cup - do Egyptians feel that the 33-year-old now needs to deliver on the international stage?

"Salah has already done his legacy. Hes the greatest Egyptian footballer in our history," says Mido.

"He doesnt have to prove anything to anyone, hes a legend for Liverpool and a legend for Egypt."

Salah takes a selfie in front of Liverpool fans after the clubs 2024-25 Premier League title triumph