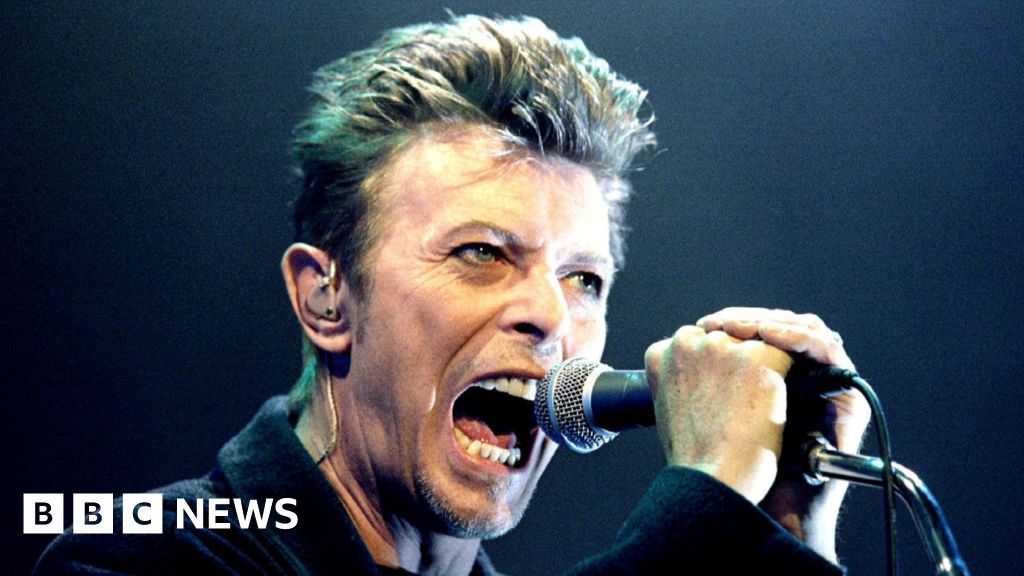

David Bowie’s secret final project discovered locked in his study

- BBC News

When David Bowie died in 2016, his parting gift was a final album, Blackstar, shaped by his cancer diagnosis and an acceptance of mortality.

But in his final months, he had also started another project, described in his notes as an "18th Century musical".

Called The Spectator, its existence was unknown to even his closest collaborators – until the notes were discovered locked in his study in 2016. They have now been donated to the V&A Museum, with the rest of Bowies archive.

Shared exclusively with the BBC, they show Bowies fascination with the development of art and satire in 18th Century London, alongside stories of criminal gangs and the notorious thief "Honest" Jack Sheppard.

Had it been completed, the musical would have realised one of Bowies lifelong ambitions.

"Right at the very beginning, I really wanted to write for theatre," he told BBC Radio 4s John Wilson in 2002.

"And I guess I could have just written for theatre in my living room – but I think the intent was [always] to have a pretty big audience."

Bowies notes for The Spectator were found as he had left them, pinned to the walls and stored in his office in New York.

The room was always locked – only Bowie and his personal assistant had a key – so they were left undisturbed until archivists started cataloguing his belongings.

They will be available for fans and scholars to view when the David Bowie Centre opens at the V&A East Storehouse in Hackney Wick on 13 September.

"We even have the desk [where he worked] at the Storehouse, as well," says Madeleine Haddon, the collections lead curator.

An entire notebook is devoted to The Spectator, a daily periodical that ran for 555 issues between 1711 and 1712 commenting on the manners and fads of London society.

Writing in black pen, Bowie summarised several of the publications key essays, scoring them out of 10.

He particularly enjoyed a morality tale about two sisters – one beautiful but "vain and severe", who lost a suitor to her plain, but more agreeable, sibling.

Awarding it eight out of 10, Bowie commented, "could be a good subplot".

He was also amused by a report concerning a Mr Clinch of Barnet, who could imitate the sounds of horses, hounds, an old woman and a bassoon "all with his own natural voice, to the greatest perfection".

Prof Bob Harris, a historian and 18th Century specialist at the University of Oxford, says he can understand why the period caught Bowies attention.

"London, at that stage, was such an exciting, vibrant and diverse city," he says.

"It was the largest city in western Europe, with a population of over half a million, and it had an ebullient print media that was constantly commentating on the fashions and follies of the age."

Bowie was particularly fascinated by crime and punishment.

In one note, he envisaged the aftermath of a public hanging, with "surgeons fighting over corpses".

He also considered making Jack Sheppard, a petty thief who had won the publics affection, one of the main characters. He also references "thief-taker general" Jonathan Wild, a vigilante who was responsible for Sheppards arrest and execution.

Another possible plot point involved a "central figure" in the musical being attacked by a notorious gang known as the Mohocks.

"The Mohock phenomenon emerged in 1712 and became a media frenzy," says Prof Harris.

"And what it involved was young men of high social status basically getting drunk in the evening and then attacking people on the streets of London, often women, sometimes elderly Watchmen.

"London threw up so many different juxtapositions. Juxtapositions between high and low, between the virtuous and the criminal, and these things existed cheek by jowl.

"I think it presented so much that was beguiling to contemporaries, but also clearly that Bowie himself found fascinating."

On a broader level, Bowie constructed a chronology of the early 18th Century, looking at painters such as Joshua Reynolds and William Hogarth, and the creation of the Royal Academy.

"He was interested in the development of musicals themselves in London in this period, and how musicals were used for political satire, particularly towards the Robert Walpole government," says Haddon.

"It seems he was thinking, What is the role of artists within this period? How are artists creating a kind of satirical commentary?"

She speculates that the musician was drawing parallels between the Enlightenment and the modern day.

"Its interesting to think that Bowie was working on this in the US in 2015, with the political situation that was taking place there. Was he thinking about that: The power of art forms to create change within our own political moment?" she asks.

Ultimately, we will never know Bowies intentions. But the musicians archive, which runs to some 90,000 objects, will keep scholars busy for years.

About 200 items will be on display at the centre, but visitors can book an appointment to view anything from the collection in person – from stage costumes to handwritten lyrics – by filling out an online form.

"Im so excited to see the impact this will have [on] the next generation of musicians, artists, designers and creators of all kinds," says Haddon.

"If you think about how so many young people today dont want to be defined by a singular genre, Bowie really was a pioneer for that.

"I hope people take away the breadth of impact hes had on popular culture – but I also hope people will be prompted to think about the tools and processes Bowie used that they can apply to their own creativity."